Fun with PhotoDoc: Infrared (Edition 7)

At the end of last year the lab purchased a modified UV-Vis-IR Nikon through MaxMax so that we can start to play around with infrared photography. Infrared photography (IR) is commonly used in fine art conservation as an examination tool. Reflected IR can be helpful when trying to identify pigments, inks, coatings, etc. and transmitted IR can helpful for viewing watermarks, underdrawings, and linings. We’ve only just started dabbling with IR photography, but I wanted to share some photos from my most recent session with reflected IR.

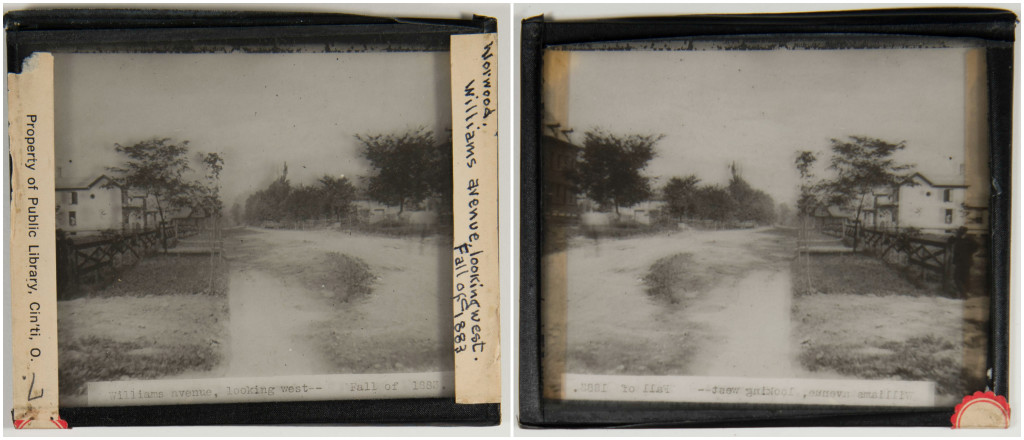

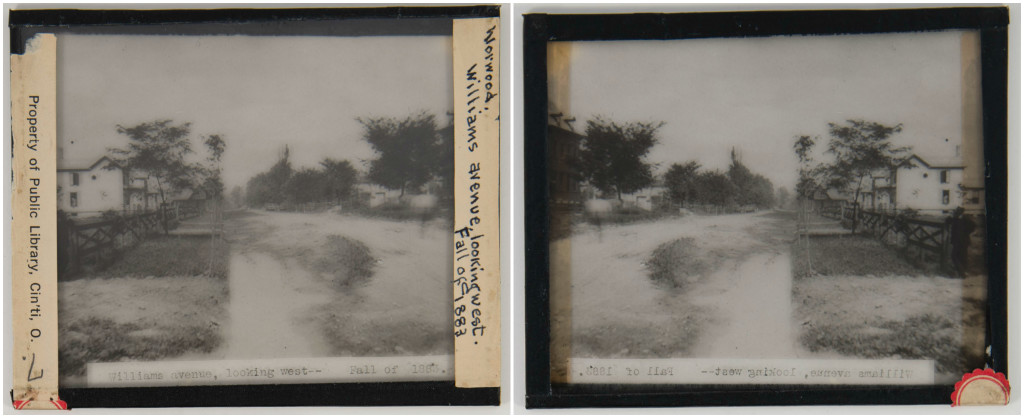

This is a full leather photo album from the Public Library of Cincinnati & Hamilton County’s collection. This early 1900s photo album contains hand-colored silver gelatin photographs taken by A. Nielen. The photographs appear to depict his travels through the US and Canada, and various landmarks and neighborhoods of Cincinnati are represented.

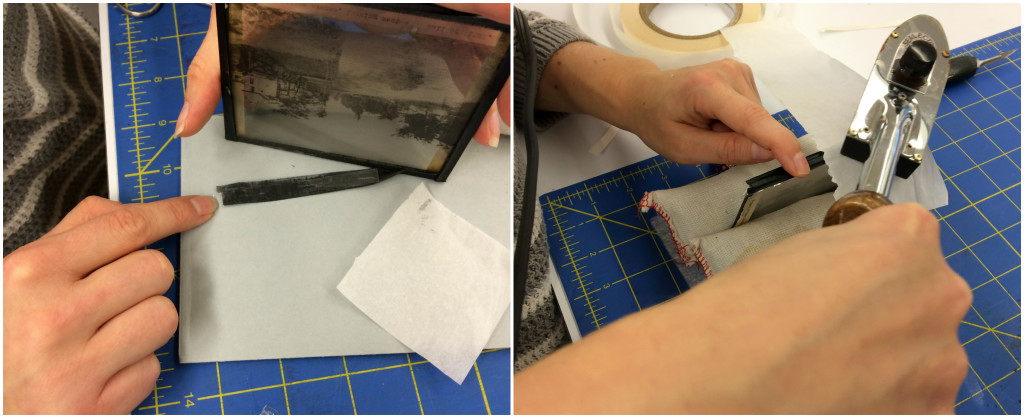

This seemed like a good object for reflected IR because of the hand-coloring on the photographs and the white ink inscription below each photograph. I began by taking a representative visible light image (first image below) using our modified UV-Vis-IR camera, incandescent lighting, and the X-Nite CC1 filter on our 50mm lens. Then, being careful not to move the position of the camera or the object, I switched to the X-Nite 830 filter (830nm) and converted that image to grayscale in Photoshop (second image below). Then I took my visible light image and my reflected IR image into Photoshop to create the false-color image (third image below). The digital false-color image is a combined representation of the visible and infrared images, and it’s actually quite simple to make. You basically copy and paste the various channels for the VIS and IR image as follows, green to blue, red to green, and IR to red. The false-color image allows you to better differentiate and characterize the various materials (pigments, inks, etc.) and potentially even identify them if you have sufficient known samples to use as references.

Like I said, we’ve only just started using IR and we’ve got a long way to go, but I’m looking forward to experimenting and learning more about it as time goes on.

Jessica Ebert (UCL) – Conservation Technician