Changes in Best Practices

One of the best parts of the formation of our joint lab was the addition of a full time conservator. The University of Cincinnati lab had been performing a variety of conservation repairs or mends on general collection items for years. Tip-ins, tears, tape removal, sewing and spine repairs were all familiar types of mending to those of us who had been working in the existing UC lab. But when our joint lab began and our new conservator, Kathy Lechuga, started we quickly began to see that not all our repairs or mends were up to par. Kathy had a vast knowledge of conservation, including best practices that were more up-to-date. Even straight forward repairs like spine repairs (or re-backs) that haven’t changed much in the last 30 years needed some minor tweaking. But one repair stuck out as needing a major update, a paper hinge repair we had been doing for years and years.

When it was originally created this paper hinge was remarkable. It could take a book where the textblock had broken away from the cover either partially or completely and with little time or money the book was in one piece again. Using two pieces of paper cut to the height of the textblock, the first sheet would cover the spine and then lay over onto the textblock, about 1/2 inch, with a beveled edge to prevent a clear break line. The second piece of paper would also wrap around the spine (adhered to the first) and the rest would be laid down onto the inside of the cover. The paper hinge was quick and inexpensive, but as we would learn from Kathy, not very effective in the long run and not of the current best practice.

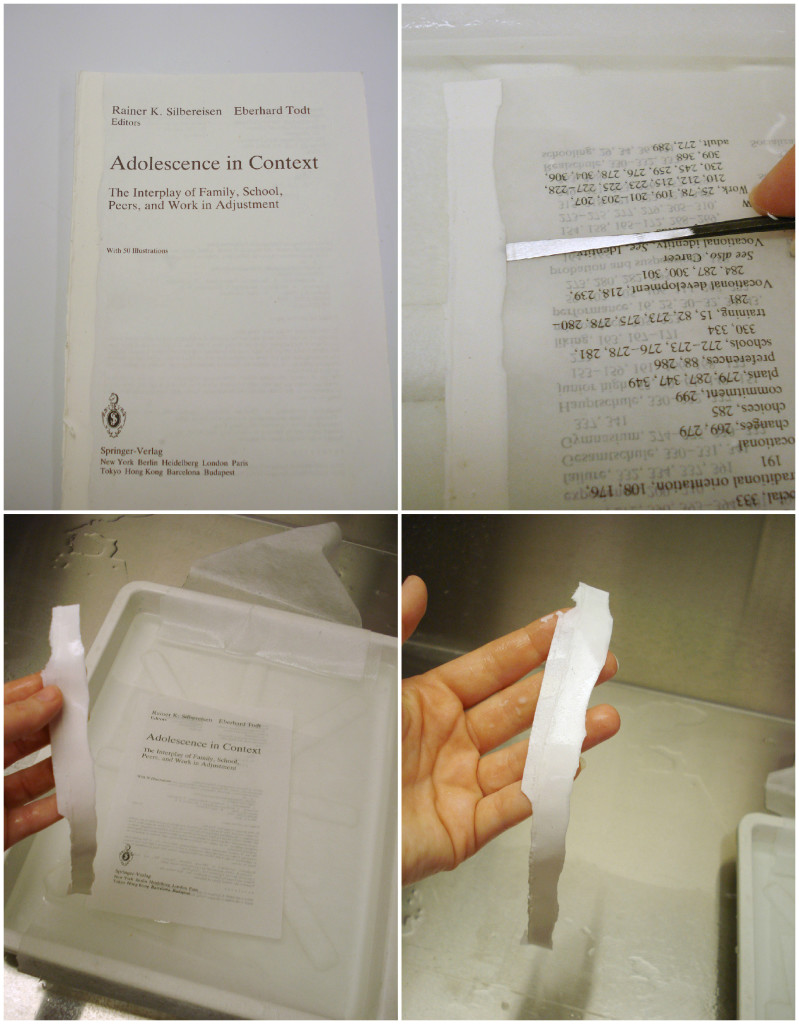

We had wondered for some time whether there was something out there that was newer and better, that would last longer and not fail as quickly, but without the knowledge of a better repair there was little us conservation technicians could do on our own. Recently, I was evaluating a UC general collections item that had previously received this paper hinge repair. It had received a “type II” paper hinge, which means it had been broken at the front and back. The paper hinge was far too stiff and rigid for the relatively thin textblock paper and overtime the textblock broke in two new spots. So, once again, we were left with a textblock that was completely separated from its cover. Now the only logical course of action for us, taking into consideration time and cost and the fact that it was an adhesive bound book, was to remove the paper hinge and send the book to our commercial bindery to be rebound. Since it was adhesive bound and the individual pages could be removed I decided to float off the old paper hinge a water bath.

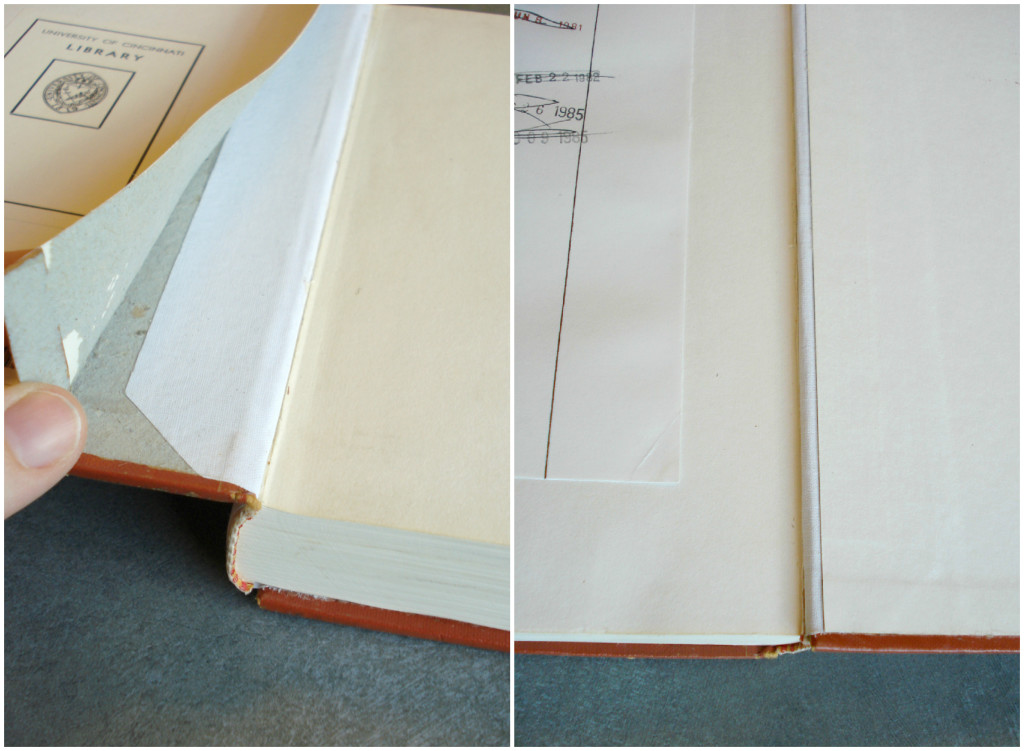

We no longer perform this type of paper hinge repair. When Kathy arrived she immediately explained to us why this hinge repair was out of date, that it placed most of the strain on the pages rather than on the spine. And then she introduced us to the cloth hinge, a current best practice in many conservation circles. Using cambric as an inexpensive but effective reinforcing material, we learned to attach the cloth to the spine and then place it under the lifted pastedowns. Since the cloth hinge is independent of the paper, the weight of the book now rests on the boards and the spine (see below).

The cloth hinge has new become a staple in our list of general collection repairs we perform. Its durability is outstanding. And while it takes just a tad more time than the paper hinge repair we were doing, it is definitely worth the effort. In some cases, especially with oversized coffee table books, the cloth hinge actually makes the book infinitely stronger than it ever was before…just like us. Before our joint lab was formed the UC lab was functioning and repairing books, but our knowledge of current best practices was stunted. But now! Now, we are moving forward, learning news techniques with new tools, and we are becoming better and stronger day by day.

Jessica Ebert — Conservation Technician (UCL)